Words Peter Hart // Photos Hart Photography & John Carter

Originally published within the June ’18 edition.

In the first of a 2 part, (and perhaps eventually multi part) series, Harty teams up with foiling experts Sam Ross and Tris Best to guide you through this insanely thrilling and accessible avenue of the sport.

First time making a board actually go … magic. First time hooking in … aaaaahh the gorgeous relief! First time planing in the straps … life will never be the same again. First time properly and wilfully airborne … this shouldn’t be possible?! First time charging downwind surfing an unbroken swell … does it get any better?! First time fully powered and in control of a 38cm wide speed board … I never knew I had that much adrenaline.

Is it is possible that after 40 years, windsurfing can still provide me with first time thrills to match that lot? Apparently it can. … first time flying on a foil, actually flying and staying up there above the ocean and yet without the sound of the ocean clattering noisily against your bow – just a gentle, eerie ‘whooosh’ – well it’s right up there with the best.

It’s possible I’m just older and therefore easier to please. On the other hand, with age also comes a natural resistance to change and a healthy scepticism towards anything new and ‘faddy.’ Foiling may be the new kid on the block but it certainly doesn’t feel like a fad. But when a new wave rolls in, the temptation is to catch it for no other reason than that everyone else has. So the first question is: is it for you? By the end of this diatribe, you should be a little better informed about the sensation and how, where, when and with what to do it with; as well as the common pitfalls. However, what ultimately decides the yes or no question is whether it has a place in your windy schedule given you ability, favoured disciplines, the winds you most favour and where you’re likely to sail.

“The best thing about foiling is that it’s laden with hilarious double-entendres. “I just can’t get up …”, “I get it up but can’t keep it up..”, etc., etc., which keeps the lads amongst us in permanent stitches.”

Where does it fit?

The general perception is that foiling is primarily about scoring planing fun in less wind – true – but it’s also about flying around with less power. With that in mind, here are windy types to which it might appeal.

The Wave Sailor

Of all the Windies, wave sailors can potentially spend the most time on the beach with folded arms staring forlornly at an uncooperative ocean. Their biggest sail is typically a 5.3 (5.8 at a push) so unless there’s a groundswell through which they can bog and then ride, their fun starts in a minimum of 18 knots. It’s much the same with the freestyler. But with a foil and a bit of practice, that same sail can get them going in 12-14 knots. It’s a lesser experience surely? No. For a start, it draws a crowd (and freestylers love a crowd). Furthermore it’s edgy, technical and the scope for eccentricity is endless. Freestyle foiling already has legs.

The Freerider

The freerider desperate for speedy water time perhaps has the most to gain, especially if he or she is looking to exploit marginal breezes. A foil will extend the experience and potentially bring relief to tendons, spine and wallet.

Take a 10 knot day, a pretty common strength in lands bereft of regular trades or thermals and for which even the scrawniest, most skilful racer needs a 9 metre plus sized sail to fully release them.

Big rigs divide the community. They’re cherished by racy types for their ability to power them on all points in a moderate breeze. Big people accept them as a necessity. For the majority, however, they’re heavy, lumbering, evil in the transitions, a nightmare to recover and just … big. Oh yes … and they’re horribly expensive. That one monster demands its own mast and boom – and you shouldn’t skimp on the hardware quality because it’s heavy enough as it is.

The general rule with foiling is that (with practice) you need 2 sail sizes less to get going. So in that same 10 knot wind you can get away with a relatively light and flicky 7.5, which takes a standard 460 mast and your existing 210 wave boom. But more than that, in my limited experience, foiling in 10 knots is a lot more exciting and challenging than semi-planing with a spinnaker.

The Elite

Tweakers and gear freaks are in heaven. Modular foils with exchangeable wings and fuselages that change the amount, nature and point of lift, offer endless tuning parameters. I’ve just been harsh about big sails but already specialised foiling rigs of 10 metres plus are emerging to bring high performance windsurfing into winds as feeble as 6 knots.

Enough of the why – lets get down to the ‘where’ and ‘how.’ But first are you biting off a little more than you can chew?

HOW GOOD?

You’ll be foiling on a board wider than 75cm, slalom style with the feet near or on the rail in the outboard straps.

So the key skill is being able to plane comfortably in the outboard straps of a 120-150 litre freeride board (more about choice of board size at the end).

The getting planing sequence on a foil is different in that you have to get into the straps very early. In the moderate winds you choose to learn in, you won’t start to fly until the back foot is in or at least over the foil. So being able to step daintily into outboard straps without upsetting the trim is the key skill.

Tris has something to say about the required standard:

“Foiling does bring different sensations. Coaching at the centre we find the lower intermediate, relatively new to the sport, often does better initially than the experienced freerider because they are less set in their ways and react more instinctively to new pressures.”

Where?

The ultimate advantage of foiling is surely to ride over, not clatter into all that horrible short spaced chop. However, when you’re starting out, chop, slop, mush or real waves, just as when mastering the regular game, are variables you can well do without. On flat water, you generate more speed more quickly; it’s easier to hold trim and much easier to slip into the outboard straps without the heels catching the water.

You also need a bit of constant depth. Foils are between 70 and 100cm deep (soon to be deeper) so you need at least 120cm of water to get launched. Random sandbanks, reefs and lobster pot ropes are even worse news for foils than for fins. For those very reasons, reservoirs are turning out to be a real hit. Of course foils draw a lot less when flying but you gotta come down sometime.

“The only way to answer that knotty question, “Should I give it a go?” … is to give it a go. But the go you give it must be a proper one and undertaken with the same resilience and open mind with which you attacked the sport in the first place – that is to say a willingness to fail, brush yourself down and go again.”

ANATOMY OF THE FIRST FLIGHT

I hesitate at this early stage of my career to use myself as a good example, but everything in the shot, the kit, the weather and the technique advice, has made flying as achievable as it’s possible to be. Click image below

THE RIGHT START

Sam is the foremost UK foiling pioneer and has this to say about learning:

“I can basically teach you in 2 hours what it took me 5 months to work out. Starting out with no knowledge I thought, I want control, so I went for a low boom, long lines, and straps forward – it didn’t work … but I didn’t know it didn’t work! I assumed it was clearly a technique issue … but it wasn’t.”

Just like normal windsurfing, most issues are kit related. Remember what it was like learning to plane. If the sail was badly set, unstable or too big or small for the board which had too big or too small a fin; and if you were connected to it all by ill-set harness lines of the wrong length, it was impossible to hold trim and line without assuming agonising body shapes. But when someone retuned you and balanced out all those pressures, how much easier was it to find a comfortable symmetry? Foiling is just the same – all we’re doing is trying to balance forces to give us the best possible chance.

Here’s a clue – it’s not just about the foil.

Going into a shop and asking ‘what foil should I get’ is as ridiculous as a beginner asking what fin he needs when he hasn’t even got a board or had a go. It’s a question that simply invites a hundred others. What board are you using with what size sail etc. etc.? So easily the best approach is to take a lesson and be handed the right kit. Knowing the foil, board, rig and general setup is right for each other, you and the conditions means you attack with total confidence in the knowledge that flight is possible and probable.

Tris: “We’ll set someone up to get instant flight where the foil is stable and progressive. But their progress is so meteoric that after even the first session they could consider something more challenging – so that’s why it’s best to gather a bit of experience and knowledge before committing to a purchase.”

Technical knowledge is pretty irrelevant until you’ve felt the feeling.

In the next issue we’ll talk more intimately about kit and setup options – unsurprisingly it does make a huge difference. But for now I will focus only on the elements relevant to the experience of getting that first sustained flight.

UP SHE COMES

The essentials of taking off are holding the rig still and away from you on extended arms – and then getting straight into the straps and pumping the foil. Note as soon as the windward edge lifts, Sam straightens up and locks out.

(Left) Pumping across the wind – don’t bear away too much – on extended arms.

(Right) And then stand tall, hinge at the waist, pressure the heels and lock out as you rise up.

UP AND AWAY

In between ‘Beasts from the East’ this past March, I met up with Sam and Tris over 2 days at a chilly Portland Harbour, which given its calm, mostly deep and ‘sheltered from waves but not wind’ waters, is probably the best foiling area in the kingdom.

The instructor training week (for instructors who had never foiled) was only a day old but the candidates were already flying. (You’ve already surmised that

‘flying’ in a foiling sense means up and riding on the foil – not ‘flying’ in a crazy, warp speed, out of control sense … although there was a bit of that as well).

The wind was between 8 and 15 knots and they were all out on rigs between

7.5-8.0. That was a surprise. It’s time to bust a myth.

Power – your first friend

Early PR tales inferred that you could be up in 6 knots of wind with your 4.7. That just doesn’t happen. The truth early on is that to learn effectively you want 10-15 knots of wind and to use almost the same size rig as you would sailing normally. Learning to plane, it’s so much easier with a bit in reserve to grind the thing out of the water despite your leaden, stomping feet. Eventually you can get planing with less power but only when you’ve developed a feel for the trim and how, when and where to direct the power. It’s the same with foiling.

The mantra for learning is ‘fail quicker better.’ It won’t be music to the ears of the timid but everyone who gets it quickly flies up on the foil, cavitates and crashes. That is success! Until you’ve felt the feedback from the foil, you can’t learn to control it.

Sam: “When first trying it out, I was under the impression I could get up using my 5.6 wave sail in 12 knots (and maybe now I could). I pumped so hard that I actually threw up on the beach! If I could write a retrospective note to my learning self, it would be ‘take more sail!’”

Let’s be quite clear that foiling is not out to replace regular board-to-the-water windsurfing. It’s just another discipline, another sensation and a new avenue to be explored.

THE MANDATORY FALLS

‘Fail faster, better.’ That’s the mantra. You can’t learn until you’ve got it up – and when you get it up, you will have a small panic attack followed by a technical meltdown and come back down with a hint of violence. But success! You’ve flown! But the two classic falls, windward edge down and leeward edge down (and roll) have easily recognisable symptoms and, with a clear head, are readily curable.

(Left) As you rise, the instinct is to bend the legs – and by so doing the windward edge continues to rise. Don’t! Straighten the legs and lock the ankles.

(Right) If you bend the arms, pull the rig to windward and get too close to it, you’ll drop the windward edge. Hold the rig forward and away from you.

SAFELY SPEAKING

When I first had a go, the accepted wisdom was to wear a helmet because … well, who knows what may happen? It’s still a wise precaution and may also prompt you to be a little more daring – but no longer seems mandatory. The obvious worry is that the foil is a big, deep, solid piece of hardware with a variety of sharp edges in unfamiliar places. But neither the foil, nor the activity itself, need be injurious so long as you adhere to certain rules.

1. DON’T LET GO! It’s the same advice as for looping – if you always hang onto the boom no matter the severity of the wipe out, the foil can’t get at you.

2. THE WATERSTART KICK. The wings are deeper and stick out further than a fin, so be especially careful when treading water and lifting the feet to waterstart. Boots are a sensible accessory. Uphauling is often the better option.

3. LOOK RATHER THAN LISTEN. There were 10 of us out and yet there was barely a sound – just a ‘swish’ here and a ‘whoosh’ there, like a group of Star Wars fans playing with their light sabres. We rely a lot on our ears windsurfing to the point where if we don’t hear the ‘lap lap lap’ of someone behind, we might not even bother to look round before tacking or gybing. You WON’T hear someone on a foil so MUST look before manoeuvring.

4. MORE ROOM. Tacking, or at least heading upwind, is a good way to stop on a windsurfer. It isn’t so good on a foil. Even when the sail is

depowered, the foil keeps on lifting, especially if you’re standing over it. On my first foiling tack, I made about 50 metres. You’ll need a lot more room than you’re used to. The same goes for gybing.

GETTING IT UP

Even with extra power, instant flight isn’t a given. You have to adapt in a few ways.

Feet in straps. You come off the foil and touch back down by leaning or stepping forward – so that should give you a clue how to induce flight – do the opposite. You have to be standing in the straps. Some who are unused to aggressive outboard strap positions struggle with putting the back foot in off the plane, so an alternative is to leave it out but move it right back and inboard over the foil. For regular windsurfing, keep off your back foot to get planing. For foiling – get ON the back foot.

Pumping is a different action. There is no circular rig movement. Instead, leave it forward, still and open and use it as a counterbalance from which to pump the foil. And you pump by pushing down against the foil rather than laterally.

It’s incredible how quickly the foil reacts and lifts.

Because you start flying in less wind, if you pump by sheeting the sail in, there’s no pressure and you tend to oversheet and stall. (Done that …)

Tris:“It sounds like a balancing act, but after the first couple of pumps, as soon as water is passing over the foil, it immediately becomes very stable even at low speeds and getting into the back strap is easier than it sounds.”

To help maintain control as you step back, try a different route to the back strap. Normally we’d move it back along the centre line and then outboard into the strap. But for foiling lift it up and outboard first and then back into the strap. It keeps pressure away from the foil as you start off and helps keep the windward edge down.

Bear away … but not much. You bear away a little, but not as much as for normal planing or once again you lose power. As soon as you start to fly, head up. I spend my life telling people to get off the tail, bear away as much as you think you should … and then another 90°. So that for me required a total reversal of instincts.

Let’s finish the ‘getting it up’ section with what some might call ‘over-technical’ advice:

BLOODY GO FOR IT!!! If you fanny about, the speed goes and you lose the moment.

JUST DO IT! (Don’t think about it.)

Sam and Tris noticed an interesting trend in that the instructors they were coaching made quicker initial progress than the trainers (top of the instruction ladder and all expert windsurfers) who’d they’d taught the week before. The reason seemed to be that the trainers wanted to know everything immediately, whereas the instructors just gave it a crack and reacted to what was in front of them.

The coaching method in foiling, as it should be with all coaching, is the minimum of words early on. When you first rise up on that foil, like dipping into that first loop, your head will empty of all previous instructions. But as I mentioned, with a crash can come feedback. And talking of crashes …

Obvious Crash Symptoms

In a happy way, foiling is much like the duck gybe in that there are 2 classic errors leading to 2 crashes with easily identifiable symptoms (in the duck it’s either a premature or tardy rig release).

In foiling the 2 crashes are:

1. Windward edge lifting and you rolling/catapulting to leeward over/into the rig.

2. Windward edge suddenly collapsing and catching.

The windward edge lift and catapult

You will do it – it’s mandatory. When you first start to lift off, adrenalin dilutes logical thought and instinctively you bend your knees (and probably arms and waist as well) – probably because in regular windsurfing when the board rises with a wave, we try to maintain board water contact by sucking up the bump with soft knees. Whatever – it’s wrong. If you bend the knees and compress, the windward edge will keep lifting. Instead you must straighten the legs and with the heels over the edge, hinge at the waist and lock the ankles down.

Windward edge drop

This arises from bending the arms, getting too close to the rig, oversheeting and stalling. The tip is to keep the rig upright, still and away from you.

SUSTAINED FLIGHT

The general advice to first time foilers is to stop being a windsurfer. Just relax, empty your head of preconceptions and treat it as a totally new thing. Then having changed a few reflexes and worked out how to hold your trim and adjust your height, you gradually turn back into a windsurfer and tap into those squillions of hours of practice. Moving back to step one – that is to say rising up and then levelling off nose to tail – these are the various elements that make it happen.

Rig still

The less you move the rig, in both the fore/aft and especially the windward/leeward plane, the easier it is to hold everything level. To generate speed, remember, pump the foil not the sail.

Control the nose

As you rise up, logic tells you, that because there’s nothing supporting the nose, that in order to lower your height, you surely sheet out and lean back. No! If you drop onto the back foot, you’ll load up the foil and get blasted upward again. To control height, you have to get pressure forwards. Here are three things to think about.

The Head. You’ve heard this one a million times but head position controls all.

By looking forward and upwind, you naturally commit to the harness and keep the hips forward and outboard.

Underhand front hand. It’s back to the 80s here. You can pump with overhand grip to extend the rig further forward but then swap to under hand as you rise up, because it naturally makes you pull down on the boom.

Front hand forward and back. Here’s the real game changer – using the position of the front hand to control height. Forward to lower your height, back to come up again. In normal windsurfing putting the front hand forwards on the boom is such a cardinal sin (leaves you too close to the rig, makes you head up and choke power in a number of moves), that we rule it out as a potential trimming tool (apart from moving it forward prior to the rig flip). However, when foiling, it was just by moving the front hand forward that I got my first sustained flight across the harbour.

“Your aim is to quash your natural windsurfing instincts and just feel and react to the different forces.”

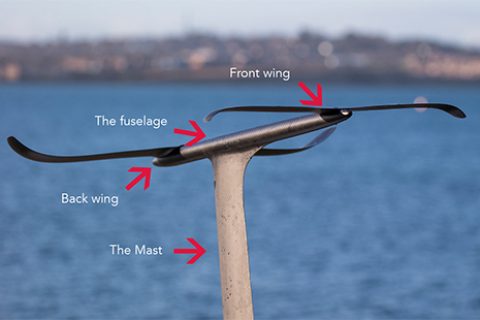

LANGUAGE LESSON

‘With foiling comes new techniques … and terms. To help you join in the conversations, here’s a quick language lesson.

THE FOILING STANCE

Just like the standard game, there is no one foiling stance. Different foils and setups produce different loads and you adjust your stance accordingly. However, starting out, certain things are immediately different from what you might be used to. I liken it to the classic Div 2 upwind stance of the 80s and 90s – that is to say tall, hooked into short lines, hips high standing right over the rail with a slight hinge at the waist.

Sam: “You know the game where everyone draws a bit of a body, folds it over and then passes it on – so the end result is a strange mish mash of everyone’s ideas. The foiling stance is a bit like that.

Feet are as if you’re stacked, heels locked down.

The legs are like you’re underpowered, dead straight and rigid.

The upper body leaning forward like you’re underpowered going upwind.

The head is cranked to windward like you’re stacked.

They’re all bits you’ve done before but not in that order!”

Crashing is an essential part of the process. Enjoy it – just don’t let go of the boom and give yourself plenty of room.

FLIGHT CHECK SUMMARY

That was a lot of words – but it really can be a lot simpler than it looks or sounds. So here’s a summary of the most common beginner errors and the cures.

1. Believing the hype and going out way underpowered.

2. Leaving the back foot forward out of the strap because it feels more controlled. But in marginal conditions unless your back foot is in, or at least back over the foil, you’re not coming up.

3. Bearing off too much to get going.

4. Bending knees and going generally floppy as you rise up. Stay rigid!

5. Staring at the rig and flopping inboard. Look upwind!

SAM ROSS – Foiling Pioneer

Sam is undoubtedly the UK’s foiling Svengali having gone through months of trial and grind so that others may benefit with a fraction of the effort.

“I’ve always thought ‘I’ll be happy when I can……..’ in windsurfing. But as you work towards each milestone another pops it’s head above the parapet. Foiling has not just allowed new opportunities to learn, but re-learn some of my favourite things in the sport. What’s been even better is helping re-teach these things to fellow windsurfers and instructors. No matter what the level of the participant the excitement in achieving the outcome is universal. It’s amazing to see now we have a grip on what to do and how things work, how quick this progression is. It’s great the RYA have got involved and I’m looking forward to seeing newly trained instructors helping people, start, continue or even revisit some of the best areas of our sport; albeit this time, flying above the water.”

Sam 2 years ago at Portland already proficient despite struggling with a desperately heavy old Formula board. The helmet has gone!

PHOTO Hart Photography

KIT TALK

You don’t need to understand the workings of the internal combustion engine to learn to drive. Likewise with foiling, a lot of technical knowledge to start with is an irrelevance. However, once I’d burst through the total idiot stage, the

windsurfer in me was immediately curious to tweak the setup and try a variety of different foils with various rig and board combos. The differences were marked and interesting.

We’ll go into setups in more detail next month, but to finish, here are some basic considerations to wet your appetite.

Boards

Very wide boards (85-100cm wide) need more power to get them up and going and it’s more of a technical challenge getting into the straps, but the board and foil are easier to control when up. Narrower boards fly more easily with less power, but are harder to control when up. The board must have enough volume to support you and give you off the plane speed and lift, otherwise you’re pumping like an idiot just to stay afloat. A good minimum volume guide is your weight plus 40 in litres and at least 75 cm wide.

Many are buying old slalom or Formula boards. The current requirement for most foils is a deep Tuttle Box (although some may soon fit Power Boxes). The foil does load the box differently and some have failed. The advantage of a ‘foil ready’ board is that the box is reinforced in the right areas. Also it’s more rounded in key areas to make touching down a smoother experience.

TRIS BEST – instructor extraordinaire

Tris Best’s OTC set up in Portland Harbour is beyond perfect as a foiling haven. He’s committed 100% to the discipline with mind, body and wonga. I don’t know what the collective noun for foils is but the OTC centre has a massive selection. Not only can he fly them all with style but he has become a fountain of technical knowledge.

Rigs

The best rigs are soft and reactive with a lot of bottom end and preferably a higher centre of effort. Bagged out cam-less wave sails and all-rounders work fine – good for getting going although not the most stable when up and riding. The best compromise between softness and stability is a single or twin cam rig. The worst for learning are fully cammed, solid race sails.

Foils

The can of worms is open but let’s stick to the basics.

Masts. The shorter masts (70cm) can be easier to learn on. They don’t rise as high making the initial experience a good deal less scary. The disadvantage of being lower is that you touch down more easily. The longer the mast, the wider the board you need.

Fuselage. The longer the fuselage the further forward the point of lift, which makes for a more stable and progressive ride – the board is slower to rise and touch down.

Front wing. Just like fins and sails, the front wing is described as high or low aspect. High aspect (long and thin) is low lift but high speed. Low aspect (short and wide) means high lift less speed. The latter is obviously better for learning, allowing you to fly with less power and at a calmer pace. And finally, a touch of personal tuning.

Boom height Keeping the boom high, shoulder and above, encourages you early on to stand tall and keep the legs straight.

Line length Crucial change here. For marginal winds I was using 26” (my regular lines are 32”). They make a huge difference forcing you to stand tall over the rail. Adjustable lines are the way to go allowing you to play with your hip height to find the perfect connection. With more wind and power you will want to lengthen them.

Footstraps They’re a key tuning device. Their position relative to the foil determines how much lift you get – forward for less, back for more. If you’re struggling to get into the straps, open them really wide and favour slightly inboard settings.

We’re up and flying and yet the surface of this new pursuit is barely scratched. In part 2 we look at the myriad of tuning options, head off up and downwind and think about flying around a tack and a gybe.

Indeed more foiling tips from Harty and his mentors next month. For clinic news and much more, head to peter-hart.com or to get in touch with the man himself, email [email protected] .