PETER HART – AFFAIRS OF THE HART – LASTING IMPRESSIONS

Peter Hart remembers the first man of windsurfing photography, Alistair Black.

“ I wager that many of you have fantasized gently about giving up the day job and becoming a full time professional windsurfing photographer. In the modern age of incredible digital cameras, how hard can it be? Surely thanks to their lightening shutter speeds, multiple frames per second and auto-everything, you just adhere to the monkeys-and-typewriters probability theory, keep your finger on the button, point it at the ocean and sooner or later you’ll luck out. You might. However, one decent shot in 10,000 won’t feed the family; and it certainly didn’t in the pre-digital age when every failed sequence cost you a tenner’s worth of Kodachrome 64. To shoot windsurfing successfully demands patience, tolerance, imagination, artistic flair, an intimate knowledge of the sport and, due to the fact that often the money shot can only be captured from the water on the stormiest days, extreme physical endurance.

It’s therefore not surprising that so many photographers who cut their teeth in windsurfing went on to excel in other fields of photo journalism. For example, Jon Nicolson went from capturing many of the early world cup speed events, to being the favoured snapper for Olympus and the Williams Formula 1 team. Andy Hooper, who produced numerous images for this very magazine in the early 90s, is now the chief sports photographer for the Daily Mail and has been UK sports photographer of the year no less than 5 times.

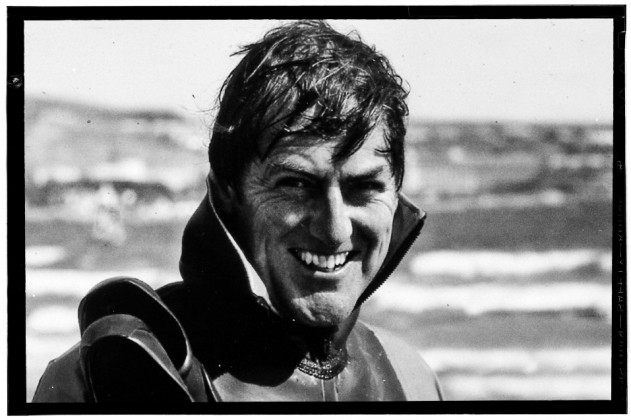

But the father of them all was Alistair Black, who recently passed away at aged 88. Not only did Alistair set the standard in terms of water photography but he also sired two famous windsurfing sons. Frazer was the first British export to Hawaii; while Ken, one of the world’s most durable and respected sailmakers, is Tushingham’s chief designer.

Alistair grew up in Campbeltown on Scotland’s west coast, where he developed his passion for the sea – and for flying. The airbase at Machrihanish (also a top windsurfing beach) was nearby. To some extent he lived his life in reverse. He started with a ‘proper’ job, trained as a dentist and served with the RAF before moving south and setting up a successful practice at Lee on Solent, where he was an active member of Stokes Bay sailing Club. Aged 40, he decided he’d had enough of staring into people’s mouths, and headed off to the London School of Art to study photography. He emerged technically informed and his life by the sea had given him a keen eye and intimate knowledge of all things wind-driven. But as he set out to make a living from marine photography, his major strength was his sense of adventure and his water confidence. While his peers contended themselves with taking chocolate box style pics of various boats from a safe distance in the comfort of a heated launch, Alistair, wet-suited up and early waterproof Nikons in hand, got properly stuck in. Ken takes up the story. “I was often his boat driver. He’d want me to get really close to the big yachts and sometimes he’d make me manoeuvre right in between the spinnaker and the hull. It was very precarious because those early racing boats were right on the edge and forever broaching. But the crews loved it and the pictures encapsulated the action like never before.”

It was of course at this time in the early 80’s that the sport of windsurfing went nuts. His son Fraser was quite a talent and was invited by Ken Winner to work at his school in Florida. It was there he was offered a place on the prestigious Mistral team and was flown over to Oahu to compete in the 1982 Pan Am Cup – the first proper, high wind, professional event.

Everyone needs a break and Alistair’s was to shoot that regatta. Conditions were extraordinary. This was windsurfing at a completely different level. Alistair’s shots of the long distance race, sailors planing on their 4m Pan Am cruisers in the massive swells off Birdshit Island as waves thundered onto the rocks, live long in the memory. Fraser was far too laid back to take the fledgling pro circuit seriously. Having made it to Hawaii, he stopped right there (and is still there 35 years later). But he was a great promotional sailor and gave Alistair an obvious excuse to make many trips to Oahu. ‘The wetter the better’ was his motto and he took residence over Diamond Head’s infamous reef.

His work soon transcended the world of windsurfing. He was twice crowned Sports Photographer of the Year and his image ‘Jump for Joy’ (a fabulously composed arty jump shot) was sports photograph of the year in 1984. His talent came to the notice of Nikon, who staged exhibitions for him in London and used many of his images in their advertising.

He had an obvious connection with windsurfing but also continued to shine in the rarified world of big boats, doing shots for Ted Heath and round-the-world legend Peter Blake.

The first time I worked with Alistair was testing ‘funboards’ in the Solent on a drizzly March morning. He had just returned from an assignment in his favourite spot, the Rangiroa atoll in French Polynesia. But despite the dramatic change of circumstances, he was as enthusiastic as a boy who had just been given his first Box Brownie. Ideas and enthusiasm flowed and you were always swept along by his passion for what he was doing. After another 20 years in a wetsuit, he retired and moved to the Isle of Wight. ‘Retire’ gives a totally false impression as he remained active and swam and played tennis right up to the last.

PH Peter Hart 4th Nov 2015