PETER HART MASTERCLASS | HEAVEN AND HELI (TACK)

The helicopter tack is a classic. It’s not only very useful in variety of situations, but also introduces you to the vital skill of backwind sailing.

Words Peter Hart // Photos Radical Sports Tobago

Originally published within the June ’19 edition.

“Thank heavens for the heli tack eh?” quipped the instructor on the shores of Vassiliki. The fabled afternoon thermal had been frustratingly absent, so by day 3 even the most jovial and imaginative instructors were struggling to add variety and spice to the endless light wind sessions. But when all else fails, there’s always the helicopter tack. It’s tricky enough to consume a few hours, and it’s entertaining. No one masters the heli tack without being drilled in a violently comical manner.

However, to regard it as just a time filler is criminal. I stand before you as leader of the ‘Helicopter Tack Defence League’. It’s a classic transition that has stood the test of time. It’s got a hint of ‘freestyley’ flamboyance, and yet is highly functional. It demands the learning of key skills such as sailing backwinded and clew first that will serve you forever. It’s also challenging without being especially dangerous. It’s readily achievable by an intermediate in 6 knots of wind; but to roll one out on a 100 litre board in 20 knots is a sure indicator of technical expertise. Where windsurfing wins over many other sliding sports, is that certain moves allow you to achieve expert status without risking your neck.

IN CONTROL BACKWINDED

A windy heli tack calls on so many skills, wind awareness, anticipation, cute rig control and very fast, precise feet. Early success stems from being able to sail, steer and control power when backwinded. Study the anatomy.

- Click to enlarge

What?

It’s a tack with a difference. You head into wind as normal, but then instead of releasing the rig and stepping around the mast, you sweep the rig forward and lean it against the wind, thereby backwinding it. You’re now on the ‘wrong’ side of the sail, resisting the pressure by pushing rather than pulling. You then use that pressure to bear away through the wind and onto the new tack. Across the wind, you ease the clew through the wind so both you and the rig rotate through 180° (that’s the helicopter bit). With your back to the wind once more, you flip the rig as per a gybe. But that description reveals absolutely nothing about the true challenge and potential pitfalls.

Why and when?

The heli-tack is my go to transition when wind is fluffy and the water’s a choppy mess. In such conditions, a standard tack calls on the finest balance and very fast accurate feet, especially when off the plane on a ‘sinky’ board. The advantage of the heli is that you have a counterbalance at all stages but notably as you pass through the wind – the most vulnerable phase. It has its limitations. Any move which involves sailing backwinded or clew first off the plane is not one best suited to crazy winds or when overpowered. The sail transition, no matter how cute your rig handling, will be like wrestling a ninja – everything happens way too fast. If you’re trying them in over 25 knots, you have to ask why. That’s the time for a downwind move or a regular tack.

HELICOPTERING SEQUENCE

Everything thing is the wrong way round. The first priority is to work out where the hell you are – only then will the tips make any sense. As you study the sequence, focus on which way the rig rotates and how you move in relation to it.

Drive the nose through the wind by sheeting in hard against the back foot. The more aggressive you are and the more speed you carry through the wind, the easier it is to backwind the sail. Note (like the normal tack) that the pressure is back but the head, hips and body are already anticipating the next phase.

Through the wind, now comes the big weight shift. Keep the sail closed as you sweep it towards the nose. At the same time load up the front foot to sink the nose and help the board turn.

As soon as the wind backs on the sail, use the front hand to drop the rig right down to windward. And use that pressure to push against the front foot and drive the nose off the wind. As the board bears away, hold the rig even further down to control the power, ease the back hand and let the clew rise right up. This is where many spin … but you’re still upwind – it’s too soon.

Bear away even more until you’re off the wind. Initiate the spin by leaning the rig even further forward, pushing gently on the back hand; at the same time dropping the shoulders back. And check the head, looking in the direction you’re about to turn.

Now is the time for calm urgency. Step around behind the mast. The feet should be in position before the sail powers up. The new back foot steps behind the front straps and the front foot by the mastfoot – both far enough back to withstand the surge of power. Coming out clew first like this, you get instant acceleration which stabilises the board …

… and makes for a calmer rig flip.

How to learn it

The methodology to learning all moves should be to see what skills are required and then practice them in isolation before joining them together. Many people attack the heli under-gunned.

The commonest sight, even at high level, is that of someone backing the sail, being met with over-powering resistance and getting slammed. It’s an experience that breeds coping mechanisms. Some manage to tick the odd box by spinning out of it the moment they get backwinded – chasing the sail around like an old dear running for the bus and just managing to get their feet in place and catch the spinning sail. But by no stretch could they ever have claimed to be in control of the situation. The issue is that they have never learned to sail, steer and control the power backwinded. And until that tool is in the box, it’s always going to be a struggle, so that’s the place to start.

Trying the heli tack for the first time in a strong wind, will just produce a series of ‘what happened there?’ moments, which will leave you bruised and none the wiser.

MAKING SPACE TO SPIN

If you can get away with it in light winds but struggle as it gets up, the problem is usually down to delaying the foot move and getting crowded by the rig. The sequence below captures the key moments just before and after the initiation of the spin.

Initiating the heli, the rig is pushed right forward and to windward, At the same time the body moves back out of the way. All the pressure has shifted to the back foot so the front foot is free to turn and step back.

With the rig forward and out of the way, you can step behind it as you open it out – not, as is the common error, just follow it around and dive off the nose.

EXTREME POWER CONTROL

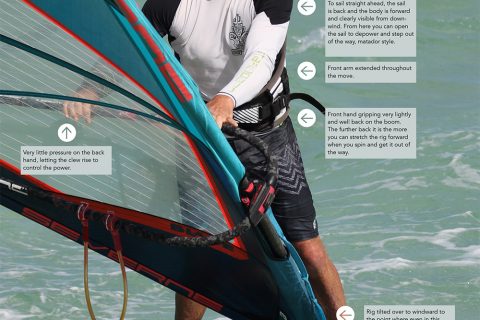

‘Bear away before spinning out of it,’ is a command far easier said than done. It’s quite a skill keeping control of the sail backwinded as you steer off the wind and demands extreme rig angles.

BACKWIND SAILING – CHALLENGE YOUR INSTINCTS

With a big board, small sail (5.3 ish for average adult) and a 5-10 knot wind, which offers pressure but not an instant penalty, get into the backwinded stance by doing a tack but without heading up. You’re now sailing across the wind, on the leeward side of the sail facing the wind, leaning towards the rig rather than against it. How long you stay there depends on your power control. The three elements are:

The windward angle

Firstly change your whole attitude towards power control. It’s less about sheeting in and out, although we are going to do that, and more about the windward / leeward angle of the rig. Your first mission is to find the balance point. Using just the front hand, lean the rig down against the wind to the point where it balances itself and doesn’t fight back. Even in a force two, it’s much lower than you think. Here lies the secret to backwind sailing – keeping the rig at arm’s length and canted well over to windward.

Even in a force two, the angle of the backwinded rig is much lower than you think.

Sheeting in and out

First focus on the back hand. A gust comes and threatens to push you backwards. Your instinct is surely to push back. So wrong. Pushing sheets the sail in and ends with you being slammed even harder. The correct reaction is to let the clew rise by pulling in the back hand.

The back hand is the evil body part in all of this, pushing when it should be pulling and forever trying to build its part. In light winds especially it does very little. The front hand is in charge. It controls the windward leeward angle and the fore and aft position – forward (towards the nose) to power up, aft to power down.

Body position and the matador

Imagine the rig as a charging bull. The worst place to be is to stand directly between it and the water when it’s going to run straight over you. Instead place yourself in front of it so you can open it and step out of the way, like a matador, with a triumphant cry of ‘ole.’ In your ‘sailing along backwinded’ stance, you should have a clear view to windward past the mast. If all you can see is sail, you’re about to be trampled.

In all backwinded moves, the challenge is to unplug the back hand and let the front hand do most of the work.

Steering

It’s less about obeying the basic instructions, which are the same whichever side of the sail you’re on (rig forward to bear away, rig back to head up) and more about feeling the changes in pressure and where you’re directing them. Move it back and the pressure pushes against the back hand, which is directed through the back foot which pushes the tail downwind. Move it forward and the power pushes against the front hand, then through the front foot (and bears the nose away). It also increases, meaning you have to drop the rig further down to windward to depower and control it.

FOOT PRESSURE AND STEERING

A general criticism of an average heli tack is the three distinct sections, the steer through the wind, the backwinding and the spin, all take too long. I refer you back to last month’s sermon on time and tempo where the key observation was that the good guys blend the sections and do everything more quickly. The two ways to speed up the heli are:

Make bigger bolder rig movements

Sliding the hands forward on the boom allows you to draw the rig further back and drives the tail harder downwind. Sliding the hands back on the boom allows you to throw the rig further forward and bear away faster – as well as put some distance between you and the rig.

Foot pressure

This makes the biggest difference. A good heli tack involves a big change of fore / aft trim. To head up you drop the back foot back and push hard to get the board to pivot on the tail. Then as you come through the wind, lunge forward and make a radical weight shift onto the front foot to sink the nose. The idea is to do a kind of flare gybe except you pivot downwind on the nose rather than the tail.

The Spin and the dance

In the heli tack you are dancing and the rig is your partner – a partner, which you hold at a comfortable distance; whom you guide gently but purposefully to one side and then move into the space left behind. The problem with the dancing/spinning phase of many helis, is that the supposed leader is hugging the partner way too close, stepping on their toes and eyeballing them with a scary leer. Don’t stare at the rig; look away and do your best to step out of its way … but how?

The circular rig action

The greatest piece of misinformation concerning the heli tack is the instruction: “push the clew through the wind.” It’s factually correct. The clew does pass through the wind. However, if you do it by thrusting out the back hand with all the subtlety of a power lifter, you just sheet the sail in and make it fight back with a vengeance. The trouble is that in the light winds in which you practise the move, you can get away with such a method … but you won’t when it freshens up. The correct ‘heli’ action is circular. You push the rig down to windward and then forward and up towards the nose. Using that circular action and just a hint of back hand pressure to guide it, the clew passes casually through the wind and rotates around. You then turn and step behind it.

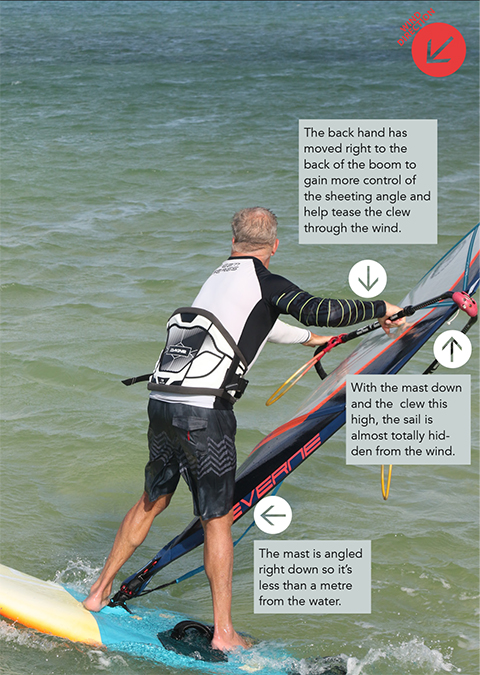

Depower … then action

If you’re nodding off, I urge you to wake up for just a moment because I’m about to reveal the secret of advanced windsurfing. Many things distinguish the experts from the improvers, but the overriding difference is power control at critical moments. Just before the rig flip, or the spin or at any time when balance is threatened, they hide and/or depower the rig. For example, you exit a gybe and are hanging back to resist a very powered up, unstable rig clew first. If you just let go of the back hand, the thing that’s holding you up suddenly isn’t there, demanding you make a violent bodily adjustment. The expert meanwhile, would ease the back hand out more gradually to the neutral point and then release it. The heli tack is even more critical in this regard because the leech has to pass through the wind. The leech, unlike the mast, is unsupported; as it comes close to the wind, it goes nuts. The wind is deciding which side of it to pass and tugs it out of shape. The windier it is, the more nuts it goes. The trick is to hide the rig by leaning right down to windward (and towards the nose) to the point where hardly any area is exposed to the wind. That’s when you ease the clew gently through the wind. And then only when the clew has passed through the wind do you bring it upright.

It’s one to practice on the beach in a stiff breeze. From the backwinded position, see how slowly and calmly you can do the rig spin. In real life on the water, you should do the whole thing quite positively and quickly – but this exercise makes it clear that if you’re fighting the power during the transition, you’re going to lose.

At the critical moment of any transition, as the sail passes through the wind, the rig should be depowered.

Anticipation

Those who have this move currently on their agendas will testify that if it’s windy, it’s hard to make it look anything apart from frantic. Again we must fall back on another windsurfing rule, which is that during a transition, you have to get your feet into position and establish a platform before the sail powers up on the new tack. Forget the niceties and project forward to the outcome. Imagine where you your feet, hips and body have to be in order to withstand the rig as it spins round clew first onto the new tack – and get them there a.s.a.p. Think – ‘feet then rig.’ Start to turn and switch the feet before the sail spins around – not the other way round.

COMMON ERROR

All of those who have fought the heli-tack and lost will empathise with the feeling of this image. It’s the moment just after the spin and just before you get drilled backwards off the tail. It’s down to the most common mistake which is doing the spin too soon and too close to the wind. The leech then catches the wind and drives you back. The solution is to bear away more before spinning.

End options

There are two ways to finish off the heli-tack. You can spin round and keep hold of the boom to end up clew first. Or you can release the rig as you spin round. The latter is easier as there’s no sudden jolt as the sail powers up clew first. You can therefore get away with being too close to the wind or having slightly slow, wayward feet. It’s also a safer option if you’re over-powered. But, it also reveals that you’re not totally in control of the end. Coming out clew first is the cleaner, slicker, more professional method – but timing, angles to the wind and feet positions have to be spot on.

For example, you have to bear away more before flipping and step the feet further back to withstand the pressure as the sail powers up. The main advantages are twofold. Firstly you have an immediate counterbalance and are more likely to survive the trickiest scenarios – chop, gusty winds etc. And secondly you generate immediate forward motion, which stabilises a small board and brings it to the surface, as well as softening the sail and making for a calmer rig flip.

And where it goes wrong….

To finish, let me pick out one common problem from each stage.

The entry, not managing to get into the backwinded position.

A lack of aggression as you head up often means the nose stops before the eye of the wind. So head up more aggressively sheeting in hard and driving that force into the back foot to push the tail away.

The board either goes backwards or heads back the other way as you back the sail.

If the board goes backwards, it could be a symptom of the above – backing the sail too soon (before the wind) – and being too tentative in sweeping the rig forward. But most commonly it’s from backing the sail by pushing too hard on the back hand, which over-sheets and stalls it. Instead keep the sail closed (don’t open it) as you sweep it forward so it knifes through the wind. Look at the wind direction and think about catching the wind with the front of the new side of the sail. And as soon as you feel that pressure, drop the sail down. It’s all done with the front hand.

Getting drilled backwards as you bear away backwinded.

First think body position. As you lean the rig to windward and backwind it, drop the shoulders over the boom into a position where you can dominate it. As you bear away, the sail wants to lift. If you let it come up even a few inches, you expose more of it to the wind and you’re toast. Feeling that lift, the right response is to push it further down with the front hand, pull it back a little and let the back hand rise up to sheet out.

You helicopter around but get pulled on top of the rig.

Again think body position. If you bend and break at the waist when you backwind the rig, you’ll replicate that position on the new tack and lose the sail downwind. Stand a little taller with your head up.

Also be aware of the rig angle. If the mast dips downwind of vertical as you spin round, in a strong wind you’ll lose it. So imagine there’s a pane of glass over the centreline of the board, which you mustn’t smash as you spin round.

Sinking the tail and being driven off the back.

This and so many related problems come from doing the helicopter bit too close to the wind. If you end up clew first heading straight into wind, the wind catches the leech and drives you backwards. The more you bear away, within reason, the easier the rig flip becomes.

In the next issue, Harty tackles a similar but yet trickier transition – the push tack. Free spaces are few and far between on his legendary clinics, but check out availability by going to www.peter-hart.com